Fragrance is having its moment. You expect to find perfume on display in drug stores, in department stores, in high end boutiques. You even find it airports at duty free shops. In a museum? That’s probably the last place you’d expect to find perfume. By the way, don’t call it perfume. I’ll explain later. Chandler Burr is the mastermind of the new Department of Olfactory Art at the Museum of Arts and Design (MAD) in New York City. His position as curator is one he created, successfully pitched to MAD in 2010. At that time, Chandler was the one and only scent critic for the New York Times, where he wrote about fragrance the same way as art, dance and book critic would write about the art they cover. Chandler’s point of view then as now, is that scents are works of art and the people creating them are artists in their own right.

Through writing “Scent Notes” for the Times, and two books about perfume, The Emperor of Scent and A Perfect Scent, Chandler says he’s seeing a growing interest in fragrance. “My life since 1998 when I completely started by chance writing The Emperor of Scent has been watching this increase.” He thought that “scent deserved recognition as art.” He pitched the idea to the major museums in New York. At MAD, he says, “They got it.” They saw that the art of perfumery and the design of the scent could be viewed as an art form as legitimate as music, literature, sculpture and painting.

Chandler mentions that MAD acknowledged that mounting this exhibition could be a risk. But they moved forward with it and The Art of Scent 1889-2012 opened on November 20, 2012. David McFadden, Chief Curator at the museum told Chandler, “this is a fascinating way to take a fundamentally new look at art and design. It is new to the public as an art.” MAD Director Holly Hotchner said to Chandler that “we are going to do for scent what has been done over the past hundred years for photography.” Will this resonate with the public? That remains to be seen. I for one, as an ardent fragrance fanatic, hope so.

There is precedence for perfume in a museum setting. The Musée International de la Parfumerie in Grasse, France, has an extensive collection, including plants and flowers used as raw ingredients. Also in Grasse, the fragrance house Fragonard gives tours of its historic factory. The Osmothèque in Versailles preserves an archive of scents dating back centuries. Baccarat displays its crystal perfume bottles at the Baccarat museum in Paris.

As you go through The Art of Scent exhibition, there is nothing to identify the scents but the scent itself. There is no fancy packaging. There are no bottles. Chandler whisked those away for a reason. “I will never ever in the Department of Olfactory Art show the bottle, the packing, the boy, the girl or any aspect of marketing whatsoever because they have nothing to do whatsoever with the work of art.” All that matters is the “juice,” what industry insiders call the liquid in the bottle. Chandler wants you to experience the scent on its own merits.

He also eschews the word perfume. “I never ever use the word perfume in any text or in speaking ever, these are works of olfactory art,” says Chandler. “It’s the same as the difference between a movie and a film. A movie is a commercial product and a film is a work of art.”

There are 12 fragrant works of art in The Art of Design. After reading all twelve of the essays I can’t tell you whether Chandler likes or doesn’t like any of the scents. It doesn’t matter. For all I know he may not like one of my favorites, Angel by Thierry Mugler, because of its huge commercial success. He says, “This is not Chandler Burr’s top 12 list.” Chandler views them as seminal works of art, seen through the lens of history and culture.

The exhibit unfolds over two rooms, the Gallery and the Salon. When you enter the Gallery, you see stark white walls with 12 big dimples. As you lean into each dimple, a motion detector senses your presence and dispenses the fragrance for you to experience. Each is labeled with the fragrance name and its creator. The innovative design was created by architectural firm Diller Scofidio + Renfro, aka DS+R, known for the High Line in New York City and many contemporary museums. Behind the walls there are 12 aroma dispenser machines using a technology developed by Scentcommunication that deliver a four second burst of fragrance. If you are worried that the room will be clouded in perfume, don’t. Chandler says air passes “over the scent oil formulation, which means the scents vanish almost instantly once they are diffused.”

In the Salon you will find a long glass table, also designed by DS+R, “where the 12 works are represented in dishes,” Chandler says. “This time visitors dip blotters (thin white paper strips) marked with the names of each work.” This interactive display lets you experience the scent over time, as each fragrance reveals its top, middle and base notes. You can even try the scent by dabbing the blotter on your skin. There is also an interactive display of the steps of creation in olfactory artist Sophia Grojman’s work of art Trésor.

In telling the story of the scents, Chandler places each in a school of art, such as Surrealism, Romanticism, Modernism and Minimalism. His essays give each fragrance context of what was happening in the cultural and artistic worlds. But he points out that movements in each school, in literature or painting for example, do not happen at the same time as the works of olfactory art. For example “Artist Ernest Beaux’s Chanel N° 5 (1921) is the greatest work of Modernism ever created in the medium of scent. Interestingly Beaux’s first major work in the Modernist style appeared eight years before Miles van der Rohe’s first major Modernist work of architecture.”

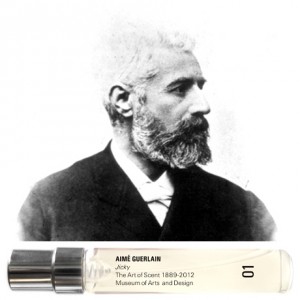

The Art of Scent begins in 1889 with the introduction of Jicky, created by Aimé Guerlain, one of the first fragrances to be made from both natural and synthetic raw materials. Chandler writes,“Guerlain, arguably the most important olfactory artist of the 19thcentury, created in Jicky one of the first two true works of olfactory art – the other being Fougère Royale (1884) – and making of scent a full-fledged artistic medium by using synthetic molecules and thus freeing the olfactory artists from the constraints of nature.” Chandler concludes, “The genius of Jicky is that it is a work that never could have existed in nature.”

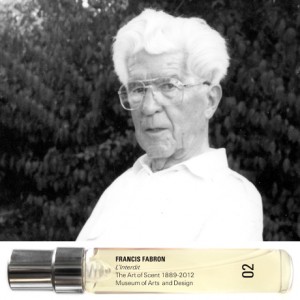

L’Interdit debuted in 1957, created by Francis Fabron for Givenchy. Chandler puts this work of art in the Abstract Expressionism school. “L’Interdit displaced the recognizable flower, wood, and grass in the way that de Kooning displaced the person, building, and landscape…Fabron intentionally departed from the natural world. L’Interdit is extraordinary for its strange beauty that ignores time. It is a work that smells as if it were made tomorrow.”

The aromatic journey continues through the evolution of modern scent into the 20th and 21st centuries.

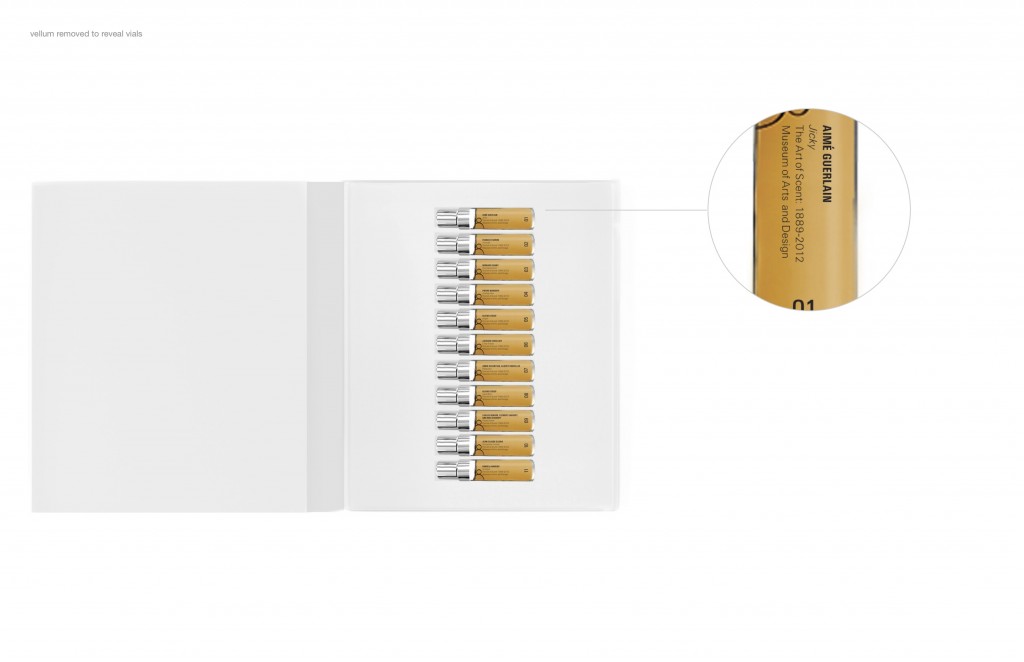

If you can’t visit the museum, you can bring The Art of Scent into you own home. Chandler has created an innovative catalog, which includes 5 ml vials of all the scents in the exhibit except for Chanel N° 5. Before now, if your read a catalog or book about perfume, you are not able to smell the aromas, unless you have a bottle of that scent with you. Chandler brilliantly solves that issue with this catalog that also includes Chandler’s essays on each scent. It’s a reference book not only for perfumistas, but lovers of art, history and culture. The Art of Scent catalog is a must have (even at $250). The exhibit runs through February 24, 2013.